PREFATORY NOTE POSTED 8.25.2019:

Hmmm… just noticed today (3.22.2020) that the “prefatory note” is gone.

I think it said something like this:

I intend to re-do this one some day, as further examples abound and I’d now start off with the fact that in Arthurian legend (in which ASOIAF and GRRM are very much steeped) there exists a knight of the round table whose “special power” is simply that he, unlike everyone else, can actually recognize his fellow knights’ faces without the aid of their heraldry. (Google “Sir Dinadan”.) Think about that: it’s a really big deal in Arthurian legend that somebody can merely recognize other people.

EDIT: I’ve begun interpolating some edits into this piece as I re-read ASOIAF for the 9th time, so there’s actually some new stuff as of 9.2.2019. When I finish my re-read, I may take a day to transfer this one to a word processor, and, leaving the body basically intact, re-do the intro, the Syrio/cat stuff, and the conclusion, then repost in its entirety.

EDIT: 3.19.2022: Re-wrote the stuff on Syrio and the Cat to better reflect what I think is going on there.

END PREFATORY NOTE, BACK TO ORIGINAL POST.

This is a greatly-expanded version of an essay I first posted back in February 2016.

If you read the original, I think it’s worth taking a look at the whole thing anyway, as I’ve made revisions throughout. The intro is heavily revised and Lyanna’s Locket is new. Everything from “Barristan vs. King’s Landing; Jorah vs. Barristan vs. The Titan’s Bastard” onward is new. In between, there are only a couple new things/revisions..

This is long, but it’s very quote-heavy after the intro, so to the extent that you’re familiar with the text of ASOIAF, it “reads” much faster than its length.

When we first read ASOIAF, most of us reflexively and unconsciously use our own practical, everyday, lived experience with identity and recognition to make sense of the text. We therefore understand identity and recognition as “naturally” relatively straightforward and unproblematic matters—to the extent we ever think about them at all. I submit that what seems to us “instinctive”—that recognition and identity are fairly simple matters—is actually not entirely timeless, innate or natural, but highly conditioned by our historical, cultural and material reality: a world saturated by accurate, easily reproducible, transportable and communicable images; a world of dense population centers and rapid transit; a world of birth certificates, fingerprints, DNA, government-issued ID cards; in short, a world of (a) readily and authoritatively verifiable identities and (b) tools which assist and allow the recognition thereof.

A transcendent, Rumsfeld-ian truism reinforces our recognition-friendly historical circumstances. Logically, we’re all ignorant of our own abject, unrectified failures to recognize people we’ve met, seen or been made aware of before. If we ever come to realize such a failure, it in that moment is already no longer an utter failure. Most total failures of recognition are doomed to remain “unknown unknowns”: we never “see” them. (I’m not talking about “I know I’ve seen her before but can’t place her”; I’m talking about not realizing I’ve seen her before in the first place.) Thus we probably have some inherent bias towards overestimating our own capacity for recognition, even as our historical circumstances reinforce the idea that recognition is easy.

Thus it’s perfectly understandable that many readers feel strongly that most tinfoil ideas regarding “secret identities” are implausible, since they can’t imagine how such a scam would possibly work out in our own world. (That such scams can and do work might tell us something, but I digress.) They argue that if a given supposed “Character A” was in fact a certain Character D disguised as or just claiming to be “Character A”, someone in the story—perhaps a specific someone who knows Character D well—would necessarily recognize “Character A” as Character D. It is sometimes argued that this hasn’t happened in ASOIAF, so there must not be any major “Character As” in the story we’re not aware of.

I submit, however, that the text of ASOIAF is clearly and pervasively saturated with instances of characters failing to recognize one another for who they “really” are. Time and again, characters not only fail to recognize other characters—whether because of assumed identities, disguises, or mere failure to announce themselves for who they are—they often don’t even think twice about it. In short, characters don’t see jack shit, and they buy what they’re fed.

There are actually countless petty instances of characters failing to recognize one another—sometimes totally, sometimes momentarily—which on the surface seem to carry minimal if any immediate dramatic weight. The basic logic of dramatic fiction (Chekhov’s Gun, essentially) suggests a greater purpose: we’re being shown that our assumptions regarding recognition and identity may be flawed and that false identities and failures of recognition are at the core of ASOIAF’s narrative and mysteries. Thus we can expect to learn there have been myriad false identities hiding in plain view of both readers and characters.

In a moment I’ll offer a few reasons why characters failing to recognize one another makes “in-world” sense. But beyond whatever “sense” we can make of this pattern, the main thing that must be grasped is that these are novels. They’re not a documentary record of real events in a real world somewhere. The only things that “happen” in ASOIAF are what GRRM decides happens, right? And the world of ASOIAF works however GRRM decides it works. If ASOIAF repeatedly shows recognition, disguise and assumed identities working a certain way “in-world”—and indeed being understood in-world to work a certain way—it only makes sense to assume the consistent examples we’re shown suggest other instances we aren’t shown. That’s how dramatic narrative functions.

Why This Makes In-World Sense

Before we look at a bunch of examples, let’s sketch out some in-world justifications GRRM might adduce as to why identity and recognition in ASOIAF work as I claim they do—and why it actually makes perfect sense.

We’re reading about a world in which images—particularly accurate images of individual people—cannot be reproduced or disseminated. There’s no mass media, no photographs, precious few portraits/paintings (of dubious accuracy). Consequently, nobody has any real idea what anybody else looks like unless they’ve met them. They might have heard about identifying characteristics—scars, coloration, distinctive facial hair, etc.—but that’s not the same as knowing what someone’s face actually looks like. (I imagine this is especially difficult for fans of the TV show to internalize, since visual recognition is intrinsic to their entire sense of who characters are.)

This is why heraldry is (and historically was) so crucial. Lords, Ladies and Knights are “recognizable” primarily by their banners, coats of arms and the obvious deference paid by those wearing their livery. Indeed, there are a bunch of examples in the text in which characters literally think about “recognizing” (or not) various sigils. For example:

Across the Mander, the storm lords had raised their standards—Renly’s own bannermen, sworn to House Baratheon and Storm’s End. Catelyn recognized Bryce Caron’s nightingales, the Penrose quills, and Lord Estermont’s sea turtle, green on green. Yet for every shield she knew, there were a dozen strange to her… (COK C II)

Even when individuals have met before, years or decades often separate those meetings, and in the interim there is probably nothing to reinforce one’s memories. No wallet photos nor photo albums, and certainly not their constantly-updated, online digital equivalents. No “Missing” or “Wanted” posters when characters are (get this!) missing or wanted. Nothing. In the meantime, mental images blur, become confused, morph and conflate. When someone “known” is eventually seen again, a similar context to the last sighting or memory can help trigger one’s hazy memory of them, but just as surely a dissimilar context might keep a blurred memory comfortably buried.

It’s impossible to overstate how much this differs from contemporary life. We can’t just magically extricate our understanding of recognizing one another from our material circumstances: a world saturated with the infinite reproducibility of precise images, in which rapid travel and population density mean thousands of faces are seen and re-seen every day. That is not how Westeros (nor our pre-modern world) works (worked).

Ultimately, though, this is merely a theoretical notion about identity, unless it can be shown that our fictional text “agrees” with it. So let’s turn to said text, which spells out its “agreement” in no uncertain terms.

The bulk of this essay will detail instance upon instance of nonrecognition and misrecognition, but before proceeding, let’s first quickly look at two of the only instances in which the text might be said to contradict my statement that there are “no wallet photos” to help with memory, both of which “just so happen” to involve the same character while problematizing both the “wallet photos” and the memories involved.

Lyanna the Locket, Lyanna the Statue

Renly’s locket is the exception that proves the “no wallet photos” rule in every respect: not only is it a unique, aberrant instance of a character possessing the purportedly accurate, easily transportable image of another, thus rendering the dearth of similar “wallet photos” all the more glaring, but Renly has been told that Margaery, or at least the locket, resembles Lyanna, whereas it turns out this is at least mostly bullshit, as Ned has no idea what he’s talking about, thus highlighting the untrustworthiness of Renly’s sources’ memories:

[Renly] had taken Ned aside to show him an exquisite rose gold locklet. Inside was a miniature painted in the vivid Myrish style, of a lovely young girl with doe’s eyes and a cascade of soft brown hair. Renly had seemed anxious to know if the girl reminded him of anyone, and when Ned had no answer but a shrug, he had seemed disappointed. The maid was Loras Tyrell’s sister Margaery, he’d confessed, but there were those who said she looked like Lyanna. “No,” Ned had told him, bemused. (GOT E VI)

Evidently “there were those” who thought they recognized Lyanna in Margaery, but the passage of time and the existence of easily recalled/communicated but ultimately superficial details like, perhaps, “long brown hair” and “pretty” are enough to allow the conflation by people who didn’t live with Lyanna for years. And it remains that while Ned’s memory of Lyanna is probably better than whomever is feeding Renly his information, it isn’t necessarily infallible. Perhaps it’s been colored by staring at the same imperfect statue of Lyanna for the past 15 years.

These twinned ideas—that physical representation in ASOIAF is a rare and inexact science and that characters’ memories (and hence abilities to recognize one another) are imperfect at best—are also manifest when Ned shows Robert Lyanna’s statue: the fidelity of both the statue and of Robert’s memory are impugned.

There were three tombs, side by side. Lord Rickard Stark, Ned’s father, had a long, stern face. The stonemason had known him well. He sat with quiet dignity, stone fingers holding tight to the sword across his lap, but in life all swords had failed him. In two smaller sepulchres on either side were his children….

Lyanna had only been sixteen, a child-woman of surpassing loveliness. Ned had loved her with all his heart. Robert had loved her even more. She was to have been his bride.

“She was more beautiful than that,” the king said after a silence. (AGOT E I)

First, it’s telling that two of the only instances in the text of a character being physically rendered (and certainly the two most prominent, Illyrio’s statue notwithstanding) involve Lyanna: the repetition invites examination.

Second, obviously we’re being shown that Robert idealizes Lyanna, but as ever GRRM is capable of saying something obvious and something subtle simultaneously. Thus it’s literally noted that Rickard, specifically, was known well to the stone-mason, but given the text’s pregnant silence (the sentence could easily have been reworded to capture all three), it’s wholly open whether the same applies to Brandon and/or Lyanna. While Ned discusses Rickard’s statue, he discusses Brandon and Lyanna themselves and not their likenesses. The text thus constructs a contrast, and then it out-and-out tells us via Robert that Lyanna’s statue is imperfect. Sure, Robert’s memory is rose-colored, but at minimum that tells us something about memory in ASOIAF in general. And on the page it’s the stone-mason’s memory of Lyanna that’s indicted. The inscrutability of the truth is the point: neither Robert’s nor the stone-mason’s mind’s eye is infallible.

A Litany of Errors (of Recogntion)

The remainder of this essay consists of detailing a rather shocking number of occasions in which characters faculties fail them, at least temporarily, causing them to not recognize people they arguably “should”. I make no claims that the list is exhaustive. You’ll notice many of these instances of nonrecognition and misrecognition are quickly and/or easily resolved. I know that. That doesn’t obviate the fact that in this work of intentional fiction, the author chose to write all these instances of characters not being recognized for who they are, even if only for a short time or by some “obviously” ignorant person(s). Indeed, it’s the pervasiveness of precisely these narratively-inert vignettes that suggests the greater purpose of foreshadowing far more momentous issues of recognition to come.

Jon Snow vs. Glamored Mance: Magic as an Analogue to Mundane Recognition

Mel explains to Mance that even though glamors are magic, they are far more effective if there is some concrete, physical artifact—context, in a sense—on which to “hang” the suggestion. In this sense, even the functioning of magical disguise mirrors something the text is saying about recognition: context is key.

“The glamor, aye…. Must I wear the bloody bones as well?”

“The spell is made of shadow and suggestion. Men see what they expect to see. The bones are part of that…. The bones help,” said Melisandre. “The bones remember. The strongest glamors are built of such things. A dead man’s boots, a hank of hair, a bag of fingerbones. With whispered words and prayer, a man’s shadow can be drawn forth from such and draped about another like a cloak. The wearer’s essence does not change, only his seeming.” (ADWD Melisandre I)

Even without magic, men’s “seeming” is regularly shown to be a matter of suggestion and expectation.

Jon vs. Real Rattleshirt

Tellingly, GRRM also shows us that “the bones” are a huge part of why the real Rattleshirt is recognizable as “Rattleshirt”:

Lord Slynt’s small eyes studied him. “Ser Glendon,” he commanded, “bring in the other prisoner.”

Ser Glendon was the tall man who had dragged Jon from his bed. Four other men went with him when he left the room, but they were back soon enough with a captive, a small, sallow, battered man fettered hand and foot. He had a single eyebrow, a widow’s peak, and a mustache that looked like a smear of dirt on his upper lip, but his face was swollen and mottled with bruises, and most of his front teeth had been knocked out.

The Eastwatch men threw the captive roughly to the floor. Lord Slynt frowned down at him. “Is this the one you spoke of?”

The captive blinked yellow eyes. “Aye.” Not until that instant did Jon recognize Rattleshirt. He is a different man without his armor, he thought. (ASOS Jon IX)

Utterly direct verbiage like “He is a different man” suggests the ease with which identities in ASOIAF may be adopted… or perhaps more importantly to the big picture, shed.

Sansa vs. Arya

We’re given a hint regarding how tricky recognition is in ASOIAF in Sansa’s very first POV chapter.

Beyond, in a clearing overlooking the river, they came upon a boy and a girl playing at knights. Their swords were wooden sticks, broom handles from the look of them, and they were rushing across the grass, swinging at each other lustily. The boy was years older, a head taller, and much stronger, and he was pressing the attack. The girl, a scrawny thing in soiled leathers, was dodging and managing to get her stick in the way of most of the boy’s blows, but not all. When she tried to lunge at him, he caught her stick with his own, swept it aside, and slid his wood down hard on her fingers. She cried out and lost her weapon.Prince Joffrey laughed. The boy looked around, wide-eyed and startled, and dropped his stick in the grass. The girl glared at them, sucking on her knuckles to take the sting out, and Sansa was horrified. “Arya?” she called out incredulously. (GOT S I)

Jason Mallister vs. Catelyn

Jason Mallister looks right fucking at Catelyn and he doesn’t even begin to recognize her:

“An inn,” Ser Rodrik repeated wistfully. “If only … but we dare not risk it. If we wish to remain unknown, I think it best we seek out some small holdfast…” He broke off as they heard sounds up the road; splashing water, the clink of mail, a horse’s whinny. “Riders,” he warned, his hand dropping to the hilt of his sword. Even on the kingsroad, it never hurt to be wary.

They followed the sounds around a lazy bend of the road and saw them; a column of armed men noisily fording a swollen stream. Catelyn reined up to let them pass. The banner in the hand of the foremost rider hung sodden and limp, but the guardsmen wore indigo cloaks and on their shoulders flew the silver eagle of Seagard. “Mallisters,” Ser Rodrik whispered to her, as if she had not known. “My lady, best pull up your hood.”

Catelyn made no move. Lord Jason Mallister himself rode with them, surrounded by his knights, his son Patrek by his side and their squires close behind. They were riding for King’s Landing and the Hand’s tourney, she knew.…

She studied Lord Jason boldly. The last time she had seen him he had been jesting with her uncle at her wedding feast; the Mallisters stood bannermen to the Tullys, and his gifts had been lavish. His brown hair was salted with white now, his face chiseled gaunt by time, yet the years had not touched his pride. He rode like a man who feared nothing. Catelyn envied him that; she had come to fear so much. As the riders passed, Lord Jason nodded a curt greeting, but it was only a high lord’s courtesy to strangers chance met on the road. There was no recognition in those fierce eyes, and his son did not even waste a look.

“He did not know you,” Ser Rodrik said after, wondering.

“He saw a pair of mud-spattered travelers by the side of the road, wet and tired. It would never occur to him to suspect that one of them was the daughter of his liege lord. I think we shall be safe enough at the inn, Ser Rodrik.” (AGOT Cat V)

Catelyn tells us why Mallister doesn’t recognize her, and it’s an invaluable lesson: Context is key.

Ned and Tyrion vs. Ser Rodrik

Characters in ASOIAF, both duplicitous and honorable, have a great deal of faith in their abilities to go unrecognized. It’s not unwarranted, or we wouldn’t be shown Lord Mallister eyeballing Catelyn blankly. But it’s actually honorable Ser Rodrik who understands that something as simple as a shave can work wonders in ASOIAF, as he explains to Catelyn just before they land in King’s Landing.

“My lady,” Ser Rodrik said, “I have thought on how best to proceed while I lay abed. You must not enter the castle. I will go in your stead and bring Ser Aron to you in some safe place.”

[Catelyn] studied the old knight [Rodrik] as the galley drew near to a pier. Moreo was shouting in the vulgar Valyrian of the Free Cities. “You would be as much at risk as I would.”

Ser Rodrik smiled. “I think not. I looked at my reflection in the water earlier and scarcely recognized myself. My mother was the last person to see me without whiskers, and she is forty years dead. I believe I am safe enough, my lady.” (GOT C IV)

So “disguised”, Ned initially fails to recognize his own master-at-arms, which is pretty crazy when you think about it, simply because his whiskers are shaved and the context—i.e. a brothel Littlefinger takes him to—is unexpected. Keep in mind, Ser Rodrik is not even trying to hide his identity from Ned—he’s announcing it.

Ned Stark dismounted in a fury. “A brothel,” he said as he seized Littlefinger by the shoulder and spun him around. “You’ve brought me all this way to take me to a brothel.”

“Your wife is inside,” Littlefinger said.

It was the final insult. “Brandon was too kind to you,” Ned said as he slammed the small man back against a wall and shoved his dagger up under the little pointed chin beard.

“My lord, no,” an urgent voice called out. “He speaks the truth.” There were footsteps behind him.

Ned spun, knife in hand, as an old white-haired man hurried toward them. He was dressed in brown roughspun, and the soft flesh under his chin wobbled as he ran. “This is no business of yours,” Ned began; then, suddenly, the recognition came. He lowered the dagger, astonished. “Ser Rodrik?” (GOT Ed IV)

The text quickly lampshades the above exchange, and this nudges readers to miss the critical thematic forest in question for the obvious tree of Ned’s putatively peculiar obtuseness:

Inside, Catelyn was waiting. She cried out when she saw him, ran to him, and embraced him fiercely.

“My lady,” Ned whispered in wonderment.

“Oh, very good,” said Littlefinger, closing the door. “You recognized her.”

While Ned is out of his depth and perhaps a bit thick, the lampshading obscures the way in which the episode is just as importantly a blueprint for such things in general.

The episode might be said to be re-lampshaded and Ned’s obtuseness reinforced when Tyrion recognizes Rodrik a short white later. Such a reading, however, misses the key fact that perspicacious Tyrion, who was around Rodrik just a few months earlier, also fails to register Rodrik’s identity until after he’s been captured by Catelyn, even then realizing who Rodrik is only when he hears his voice.

[The] black brother stepped aside silently when the old knight by Catelyn Stark’s side said, “Take their weapons,” and the sellsword Bronn stepped forward to pull the sword from Jyck’s fingers and relieve them all of their daggers. “Good,” the old man said as the tension in the common room ebbed palpably, “excellent.” Tyrion recognized the gruff voice; Winterfell’s master-at-arms, shorn of his whiskers.

A superficial change in appearance goes a long way on Planetos.

Tommen/Myrcella/Their Septa vs. Arya

Arya’s story is replete with non-recognition, beginning when Myrcella and Tommen (who know Arya) and their septa not only fail to recognize her but assume she’s a lowborn boy.

Startled, Arya dropped the cat and whirled toward the voice. The tom bounded off in the blink of an eye. At the end of the alley stood a girl with a mass of golden curls, dressed as pretty as a doll in blue satin. Beside her was a plump little blond boy with a prancing stag sewn in pearls across the front of his doublet and a miniature sword at his belt. Princess Myrcella and Prince Tommen, Arya thought. A septa as large as a draft horse hovered over them, and behind her two big men in crimson cloaks, Lannister house guards.

“What were you doing to that cat, boy?” Myrcella asked again, sternly. To her brother she said, “He’s a ragged boy, isn’t he? Look at him.” She giggled.

“A ragged dirty smelly boy,” Tommen agreed.

They don’t know me, Arya realized. They don’t even know I’m a girl. (AGOT A III)

That Arya is not Arya but a ragged boy is so “obvious” to Myrcella that she frames her opinion as a loaded, rhetorical question—something ASOIAF itself implicitly does every time it presents a secret identity it *doesn’t* announce. e.g. “This is just a ranger named Qhorin Halfhand, right?” When she says “look at him”, she is appealing to what she believes is the “self-evident” basis for that opinion. This reminds me when quality tinfoil-related catches are dismissed simply by pointing to an “obvious” reading of slippery or indeterminate syntax or verbiage and insisting it’s the only plausible reading. But ASOIAF wants us to know that thinking like Myrcella and Tommen is the wrong way to go.

That Arya is not Arya but a ragged boy is so “obvious” to Myrcella that she frames her opinion as a loaded, rhetorical question—something ASOIAF itself implicitly does every time it presents a secret identity it *doesn’t* announce. e.g. “This is just a ranger named Qhorin Halfhand, right?” When she says “look at him”, she is appealing to what she believes is the “self-evident” basis for that opinion. This reminds me when quality tinfoil-related catches are dismissed simply by pointing to an “obvious” reading of slippery or indeterminate syntax or verbiage and insisting it’s the only plausible reading. But ASOIAF wants us to know that thinking like Myrcella and Tommen is the wrong way to go.

Guards vs. Arya

Arya flees, and eventually exits the castle. She’s again not recognized and thought to be a boy when she tries to return:

Her clothes were almost dry by the time she reached the gatehouse. The portcullis was down and the gates barred, so she turned aside to a postern door. The gold cloaks who had the watch sneered when she told them to let her in. “Off with you,” one said. “The kitchen scraps are gone, and we’ll have no begging after dark.”

“I’m not a beggar,” she said. “I live here.”

“I said, off with you. Do you need a clout on the ear to help your hearing?”

“I want to see my father.”

The guards exchanged a glance. “I want to fuck the queen myself, for all the good it does me,” the younger one said.

The older scowled. “Who’s this father of yours, boy, the city ratcatcher?”

“The Hand of the King,” Arya told him.

Both men laughed, but then the older one swung his fist at her, casually, as a man would swat a dog. Arya saw the blow coming even before it began. She danced back out of the way, untouched. “I’m not a boy,” she spat at them. “I’m Arya Stark of Winterfell, and if you lay a hand on me my lord father will have both your heads on spikes. If you don’t believe me, fetch Jory Cassel or Vayon Poole from the Tower of the Hand.” She put her hands on her hips. “Now are you going to open the gate, or do you need a clout on the ear to help your hearing?” (GOT A III)

In my opinion certain identity “reveals” will surprise readers who see only what they expect to see just as much as Arya’s words surprise the guards on the gate.

People vs. A Girl, The Hound vs. Arya

I won’t quote, but after Yoren cuts off her hair Arya is able to maintain the perception she’s a boy for quite a while in the face of dozens of observers, precisely because people don’t “look with their eyes”. This bit, when Arya confronts the Hound when she’s with the Brotherhood Without Banners, is even juicier:

Arya squirted past Greenbeard so fast he never saw her. “You are a murderer!” she screamed. “You killed Mycah, don’t say you never did. You murdered him!”

The Hound stared at her with no flicker of recognition. “And who was this Mycah, boy?”

“I’m not a boy! But Mycah was. He was a butcher’s boy and you killed him. Jory said you cut him near in half, and he never even had a sword.” She could feel them looking at her now, the women and the children and the men who called themselves the knights of the hollow hill. “Who’s this now?” someone asked.

The Hound answered. “Seven hells. The little sister. The brat who tossed Joff’s pretty sword in the river.” He gave a bark of laughter. “Don’t you know you’re dead?” (SOS A VI)

Besides the obvious lesson, there’s a kind of irony here readers will eventually laugh about. Part of the reason the Hound doesn’t recognize Arya may be because she’s “dead” and thereby unconsciously excised from his brain’s “facial recognition software”. I believe the same thing is true of most readers failure to recognize several “dead”/disguised characters. (Of course, we don’t get to actually look at their faces, and GRRM hides them cleverly, so we have a better excuse.)

Arya vs. Beric Dondarrion

The Hound’s failure to recognize Arya occurs shortly after Arya, who saw Beric Dondarrion when he was in King’s Landing for The Hand’s Tourney, doesn’t “know” Beric until the Hound addresses him by name:

The walls were equal parts stone and soil, with huge white roots twisting through them like a thousand slow pale snakes…. In one place on the far side of the fire, the roots formed a kind of stairway up to a hollow in the earth where a man sat almost lost in the tangle of weirwood….

“When we left King’s Landing we were men of Winterfell and men of Darry and men of Blackhaven, Mallery men and Wylde men. We were knights and squires and men-at-arms, lords and commoners, bound together only by our purpose.” The voice came from the man seated amongst the weirwood roots halfway up the wall. “Six score of us set out to bring the king’s justice to your brother.” The speaker was descending the tangle of steps toward the floor. “Six score brave men and true, led by a fool in a starry cloak.” A scarecrow of a man, he wore a ragged black cloak speckled with stars and an iron breastplate dinted by a hundred battles. A thicket of red-gold hair hid most of his face, save for a bald spot above his left ear where his head had been smashed in. “More than eighty of our company are dead now, but others have taken up the swords that fell from their hands.” When he reached the floor, the outlaws moved aside to let him pass. One of his eyes was gone, Arya saw, the flesh about the socket scarred and puckered, and he had a dark black ring all around his neck. “With their help, we fight on as best we can, for Robert and the realm.”

“Robert?” rasped Sandor Clegane, incredulous.

“Ned Stark sent us out,” said pothelmed Jack-Be-Lucky, “but he was sitting the Iron Throne when he gave us our commands, so we were never truly his men, but Robert’s.”

“Robert is the king of the worms now. Is that why you’re down in the earth, to keep his court for him?”

“The king is dead,” the scarecrow knight admitted, “but we are still king’s men, though the royal banner we bore was lost at the Mummer’s Ford when your brother’s butchers fell upon us.” He touched his breast with a fist. “Robert is slain, but his realm remains. And we defend her.”

“Her?” The Hound snorted. “Is she your mother, Dondarrion? Or your whore?”

Dondarrion? Beric Dondarrion had been handsome; Sansa’s friend Jeyne had fallen in love with him. Even Jeyne Poole was not so blind as to think this man was fair. Yet when Arya looked at him again, she saw it; the remains of a forked purple lightning bolt on the cracked enamel of his breastplate. (ASOS A VI)

Even when she finally “recognizes” him, it’s really just his sigil that she recognizes: she’s still thinking of “Beric Dondarrion” as someone from the past, and not able to reconcile that image with “this man” before her.

Ser Donnel Haigh vs. The Hound & Arya

In ASOS Arya X, the Hound and Arya pose as a farmer and his son to get to the Twins, and a knight The Hound has faced countless times in tourneys, who has every reason in the world to “know” him and even a motive to harbor particular resentment towards him fails to see through his sophisticated disguise of… a hooded cloak.

This example is long because it’s just too packed with everything this post is about for me to trim it down. It could be the single best “lesson in (non)recognition” in ASOIAF, yet at the same time by making it about the singularly grotesque character the Hound, GRRM also invites readers to misread what’s actually being said and shown.

The outriders came on them an hour from the Green Fork, as the wayn was slogging down a muddy road.“Keep your head down and your mouth shut,” the Hound warned her as the three spurred toward them; a knight and two squires, lightly armored and mounted on fast palfreys. Clegane cracked his whip at the team, a pair of old drays that had known better days. The wayn was creaking and swaying, its two huge wooden wheels squeezing mud up out of the deep ruts in the road with every turn. Stranger followed, tied to the wagon.The big bad-tempered courser wore neither armor, barding, nor harness, and the Hound himself was garbed in splotchy green roughspun and a soot-grey mantle with a hood that swallowed his head. So long as he kept his eyes down you could not see his face, only the whites of his eyes peering out. He looked like some down-at-heels farmer. A big farmer, though. And under the roughspun was boiled leather and oiled mail, Arya knew. She looked like a farmer’s son, or maybe a swineherd. And behind them were four squat casks of salt pork and one of pickled pigs’ feet.

The riders split and circled them for a look before they came up close. Clegane drew the wayn to a halt and waited patiently on their pleasure. The knight bore spear and sword while his squires carried longbows. The badges on their jerkins were smaller versions of the sigil sewn on their master’s surcoat; a black pitch fork on a golden bar sinister, upon a russet field. Arya had thought of revealing herself to the first outriders they encountered, but she had always pictured grey-cloaked men with the direwolf on their breasts. She might have risked it even if they’d worn the Umber giant or the Glover fist, but she did not know this pitchfork knight or whom he served. The closest thing to a pitchfork she had ever seen at Winterfell was the trident in the hand of Lord Manderly’smerman.

Notice that Arya immediately looks to the men’s sigils, and literally equates not recognizing the sigil with not recognizing the knight, using the same telling verbiage that titles this essay: “she did not know” the man. Notice also that she doesn’t describe the men. She herself sees what she needs and expects to see: their weapons and the “obvious fact” (which happens to be correct this time) that they are a knight and two squires.

“You have business at the Twins?” the knight asked.

“Salt pork for the wedding feast, if it please you, ser.” The Hound mumbled his reply, his eyes down, his face hidden.

Time and again in ASOIAF people’s voices prove to be a key element of them being recognized (or not). Disguising one’s voice can be as essential as disguising one’s appearance.

“Salt pork never pleases me.” The pitchfork knight gave Clegane only the most cursory glance, and paid no attention at all to Arya, but he looked long and hard at Stranger. The stallion was no plow horse, that was plain at a glance. One of the squires almost wound up in the mud when the big black courser bit at his own mount. “How did you come by this beast?” the pitchfork knight demanded.

Here we see the effect of Clegane’s simple disguise. He’s hideously scarred are fairly obviously hiding his face, but the trappings and his manner don’t merit a second look. Notice how he says “M’lady” as if he is lowborn:

“M’lady told me to bring him, ser,” Clegane said humbly. “He’s a wedding gift for young Lord Tully.”

“What lady? Who is it you serve?”

“Old Lady Whent, ser.”

“Does she think she can buy Harrenhal back with a horse?” the knight asked. “Gods, is there any fool like an old fool?” Yet he waved them down the road. “Go on with you, then.”

Yes, this is funny, since Haigh is the actual fool here. But the humor highlights how sure of himself Haigh is, how totally unsuspecting he is of how massively important both this farmer and his “son” are.

“Aye, m’lord.” The Hound snapped his whip again, and the old drays resumed their weary trek. The wheels had settled deep into the mud during the halt, and it took several moments for the team to pull them free again. By then the outriders were riding off. Clegane gave them one last look and snorted. “Ser Donnel Haigh,” he said. “I’ve taken more horses off him than I can count. Armor as well. Once I near killed him in a mêlée.”

So this isn’t just Sandor successfully disguising his identity from a random knight, it’s Sandor doing so from a man who knows him very well and who has surely not forgotten the time Sandor almost killed him.

Moreover, how do you suppose Sandor recognizes Haigh? The text invites the easy reading that “he simply does, duh,” and thus that recognition in ASOIAF is uncomplicated and works as it does in the modern world. But I don’t think that’s it at all. I think it’s implicit that he’s able to recognize Haigh for the same reason Arya doesn’t: thanks to his sigil. Don’t misunderstand! I’m not saying he never recognizes Haigh’s face at all and simply “assumes” this guy must be Haigh because of the pitchfork. I mean that by looking at the sigil, he has a context by which he can recognize Haigh’s face and voice.

Arya asks a question that sees GRRM pull back his curtain even as he directs his audience to look away from what’s revealed:

“How come he didn’t know you, then?” Arya asked.

“Because knights are fools, and it would have been beneath him to look twice at some poxy peasant.” He gave the horses a lick with the whip. “Keep your eyes down and your tone respectful and say ser a lot, and most knights will never see you. They pay more mind to horses than to smallfolk. He might have known Stranger if he’d ever seen me ride him.”

Sandor’s analysis is sound, but it’s limited. GRRM uses Sandor’s words to both (a) show us how recognition works and fails to work, and (b) invite the “easy” reading that these circumstances are peculiar and unique, and thus don’t teach any general lessons. That is, he makes it all too easy to read the episode as being specifically about the utility of a peasant disguise vis-a-vis a haughty knight, rather than being about the general ease with which someone in disguise (as whatever!) can hide shield their true identity, and not just from haughty knights.

Arya brings up what’s really “peculiar and unique” to this episode: Sandor’s face.

He would have known your face, though. Arya had no doubt of that. Sandor Clegane’s burns would not be easy to forget, once you saw them.

The takeaway isn’t that playing a peasant to fool a knight is the perfect storm for a successful identity ruse, and thus that this ruse doesn’t teach us anything about disguises and recognition in general. It’s that despite Sandor Clegane being uniquely limited in his ability to disguise himself due to his size and the fact that he’s, y’know, missing half his face—a limitation borne out when both Marq Piper’s dying man and the village elder identify him as “Joffrey’s dog” in SOS Ary XII—Sandor both expects to fool whomever the knight is and succeeds quite easily, even when the knight proves to be a man with especial reason to hate him and to dwell on and curse his memory.

And what does this imply about most men in ASOIAF, about men who aren’t grotesquely, legendarily scarred and hence easily identifiable by even those who haven’t seen them before? It implies that most men can disguise themselves or lose themselves in a crowd far more easily, in guises far more diverse than hooded, head-down peasants, and from more people than haughty knights. Indeed, I think this is actually latent in the specific words ASOS uses to convey Arya’s certainty that Sandor’s face would be recognized.

- How so?

Arya says it’s Sandor’s quote-unquote “face” that would be recognized, verbiage which facilitates our modern, “common-sense” belief that people are easy to recognize in general. But what she means is that his hideous burns are recognizable. She literally says so: “Sandor Clegane’s burns would not be easy to forget, once you saw them.” The episode with the village elder bears this out: no one in the village has seen Sandor before; they’ve simply heard of his disfigured face.

Sandor’s mouth tightened. “So you do know who I am.”“Aye. We don’t get travelers here, that’s so, but we go to market, and to fairs. We know about King Joffrey’s dog.” (SOS Ary XII)

What do they know “about” him? The curve of his nose? The shape of his chin? Obviously not. There are no “wanted posters” or back issues of “Jousting Illustrated”. They’ve heard that Joffrey has a “dog” with half his face burned off. Here’s a giant man with half his face burned off. They can do the math.

But consider: what if Sandor’s burns were miraculously healed? How many “men” would “know him” then?

The real lesson of Arya’s properly understood statement that “He would have known your face” is its inverse: that Donnel Haigh would probably not know Sandor Clegane’s underlying, unscarred face at all; and that in ASOIAF, most people’s “faces” will not be known by those who do not know them very well, assuming they haven’t had half their face burned away.

Arya’s sharp enough to realize that Clegane’s helm is every bit as identifiable as his face, if not moreso:

He couldn’t hide the scars behind a helm, either; not so long as the helm was made in the shape of a snarling dog.

What Arya understandably fails to grasp is that people will not thereby actually recognize Sandor Clegane—they will merely assume they have recognized Sandor Clegane because they recognize his helm.

And finally she puts a bow on the importance of context, of creating expectations.

That was why they’d needed the wayn and the pickled pigs’ feet. (SOS Ary X)

Bronze Yohn Royce vs. Sansa (as Littlefinger Imagines It)

Sansa met Bronze Yohn Royce at Winterfell three or four years ago and saw him again two years ago… but Littlefinger ain’t worried:

“Bronze Yohn knows me,” [Sansa/Alayne] reminded [Littlefinger]. “He was a guest at Winterfell when his son rode north to take the black.” She had fallen wildly in love with Ser Waymar, she remembered dimly, but that was a lifetime ago, when she was a stupid little girl. “And that was not the only time. Lord Royce saw… he saw Sansa Stark again at King’s Landing, during the Hand’s tourney.”

Petyr put a finger under her chin. “That Royce glimpsed this pretty face I do not doubt, but it was one face in a thousand. A man fighting in a tourney has more to concern him than some child in the crowd. And at Winterfell, Sansa was a little girl with auburn hair. My daughter is a maiden tall and fair, and her hair is chestnut. Men see what they expect to see, Alayne.” (FFC Alayne I)

Master of schemes LF knows that a little change of context is everything in the world of ASOIAF.

“Men” vs. Tyrion in a Cloak

Despite being infamous and having an easily identifiable physicality, Varys figures Tyrion is a simple baggy, hooded cloak away from being able to travel incognito:

The eunuch took a cloak from a peg. It was roughspun, sun-faded, and threadbare, but very ample in its cut. When he swept it over Tyrion’s shoulders it enveloped him head to heel, with a cowl that could be pulled forward to drown his face in shadows. “Men see what they expect to see,” Varys said as he fussed and pulled. “Dwarfs are not so common a sight as children, so a child is what they will see. A boy in an old cloak on his father’s horse, going about his father’s business.” (ACOK Tyrion III)

The same thing applies there: Varys understands that people’s expectations vastly outweigh their ability to recontextualize their memories on the fly.

Tyrion vs. Varys

Varys’s understanding is, of course, conditioned by his own practice of constantly and successfully traveling in disguise, something we’re shown in a rare moment of failure:

A whiff of something rank made [Tyrion] turn his head. Shae stood in the door behind him, dressed in the silvery robe he’d given her…. Behind her stood one of the begging brothers, a portly man in filthy patched robes, his bare feet crusty with dirt, a bowl hung about his neck on a leather thong where a septon would have worn a crystal. The smell of him would have gagged a rat.

“Lord Varys has come to see you,” Shae announced.

The begging brother blinked at her, astonished. Tyrion laughed. “To be sure. How is it you knew him when I did not?”

She shrugged. “It’s still him. Only dressed different.”

“A different look, a different smell, a different way of walking,” said Tyrion. “Most men would be deceived.”

“And most women, maybe. But not whores. A whore learns to see the man, not his garb, or she turns up dead in an alley.” (COK Tyr X)

This is an interesting example inasmuch as somebody, for once, does recognize a disguised character. Notwithstanding Shae’s “magic whore-vision”—which is not, I think, the only reason she is able to recognize Varys, although that’s a topic for another time—notice that Varys’s disguise makes categorically no sense. Why the fuck would a begging brother show up inside her Manse in the middle of the night? That’s begging (har!) someone to look twice and question what’s going on.

This is an interesting example inasmuch as somebody, for once, does recognize a disguised character. Notwithstanding Shae’s “magic whore-vision”—which is not, I think, the only reason she is able to recognize Varys, although that’s a topic for another time—notice that Varys’s disguise makes categorically no sense. Why the fuck would a begging brother show up inside her Manse in the middle of the night? That’s begging (har!) someone to look twice and question what’s going on.

Despite that, Varys’s shocked response is revelatory: he truly assumes he is incognito as always. Tyrion’s protoyypical failure to recognize him bears out his assumption, and Tyrion fails despite seeing and working with Varys every single day and despite knowing that he’s alive, nearby, a spy and a sneak.

Ned vs. Varys I/II

The foregoing is hardly the only time Varys changes his appearance and befuddles someone who works with him daily:

The visitor was a stout man in cracked, mud-caked boots and a heavy brown robe of the coarsest roughspun, his features hidden by a cowl, his hands drawn up into voluminous sleeves.

“Who are you?” Ned asked.

“A friend,” the cowled man said in a strange, low voice. “We must speak alone, Lord Stark.”

Curiosity was stronger than caution. “Harwin, leave us,” he commanded. Not until they were alone behind closed doors did his visitor draw back his cowl.

“Lord Varys?” Ned said in astonishment.

“Lord Stark,” Varys said politely, seating himself. “I wonder if I might trouble you for a drink?”

Ned filled two cups with summerwine and handed one to Varys. “I might have passed within a foot of you and never recognized you,” he said, incredulous. He had never seen the eunuch dress in anything but silk and velvet and the richest damasks, and this man smelled of sweat instead of lilacs. (GOT E VII)

Ned’s shock is more about how much Varys’s disguise differs from his expectations of Varys than it is about the abstract quality of the disguise.

Much later Varys appears to Ned as Rugen the Gaoler. This time Ned’s a bit quicker on the draw, but he’s seen Varys in a similar disguise, Varys is not attempting to hide his identity from Ned, and recognition is still delayed and dependent on Varys’s (undisguised, apparently) voice rather than his appearance.

From outside his cell came the rattle of iron chains. As the door creaked open, Ned put a hand to the damp wall and pushed himself toward the light. The glare of a torch made him squint. “Food,” he croaked.

“Wine,” a voice answered. It was not the rat-faced man; this gaoler was stouter, shorter, though he wore the same leather half cape and spiked steel cap. “Drink, Lord Eddard.” He thrust a wineskin into Ned’s hands.

The voice was strangely familiar, yet it took Ned Stark a moment to place it. “Varys?” he said groggily when it came. He touched the man’s face. “I’m not … not dreaming this. You’re here.” The eunuch’s plump cheeks were covered with a dark stubble of beard. Ned felt the coarse hair with his fingers. Varys had transformed himself into a grizzled turnkey, reeking of sweat and sour wine. “How did you … what sort of magician are you?” (GOT E XV)

Westeros vs. Bran & Rickon

Bran and Rickon’s death are “It Is Knowns” in Westeros, but it’s all bullshit, as readers know. Those who think they saw them saw other boys entirely.

On their iron spikes atop the gatehouse, the heads waited.

…The miller’s boys had been of an age with Bran and Rickon, alike in size and coloring, and once Reek had flayed the skin from their faces and dipped their heads in tar, it was easy to see familiar features in those misshapen lumps of rotting flesh. People were such fools. If we’d said they were rams’ heads, they would have seen horns. (COK Theon V)

The Freys vs. Davos

Ditto Davos.

“Wyman Manderly has done as you commanded, and beheaded Lord Stannis’s onion knight.”

“We know this for a certainty?”

“The man’s head and hands have been mounted above the walls of White Harbor. Lord Wyman avows this, and the Freys confirm. They have seen the head there, with an onion in its mouth. And the hands, one marked by his shortened fingers.” (FFC C V)

In ASOIAF, if you “dress up” a character as somebody else, proclaim them to be somebody else, and give other characters a “hook” they can that idea hang on, your charade is going to succeed far more often than not.

Cersei vs. Her Dead Father

If you don’t believe by now that GRRM is intentionally making a point about identity and recognition we ought not ignore, perhaps this bizarre passage (in which Cersei momentarily doesn’t suss that it’s her father Tywin’s body she’s looking at) might work for you:

For a moment she did not recognize the dead man. He had hair like her father, yes, but this was some other man, surely, a smaller man, and much older. His bedrobe was hiked up around his chest, leaving him naked below the waist. The quarrel had taken him in his groin between his navel and his manhood, and was sunk so deep that only the fletching showed. His pubic hair was stiff with dried blood. More was congealing in his navel. (FFC C I)

Given a bizarre, unexpected context and/or disposition, it’s evidently possible to not register even one’s own father.

Asha vs. Tris Botley

A beard and some snow and Asha almost doesn’t recognize someone she knows very well: Tristifer Botley.

“Friends,” a half-familiar voice replied. “We looked for you at Winterfell, but found only Crowfood Umber beating drums and blowing horns. It took some time to find you.” The rider vaulted from his saddle, pulled back his hood, and bowed. So thick was his beard, and so crusted with ice, that for a moment Asha did not know him. Then it came. “Tris?” she said. (DWD The Sacrifice)

Theon vs. Asha. Asha vs. Theon.

When Theon first sees Asha in Lordsport, he of course has no idea she is the sister he lived with for the first 10 years of his life.

All he could do was stand and gape at her. Asha. No. She cannot be Asha. He realized suddenly that there were two Ashas in his head. One was the little girl he had known. The other, more vaguely imagined, looked something like her mother. Neither looked a bit like this … this … this …

“The pimples went when the breasts came,” she explained while she tussled with a dog, “but I kept the vulture’s beak.” (COK Th II)

But in ADWD, she momentarily returns the favor (as Theon notes) after Tycho Nestoris et al. ride out of the snow storm:

The Braavosi smiled. “We’ve brought a gift for you.” He beckoned to the men behind him. “We had expected to find the king at Winterfell. This same blizzard has engulfed the castle, alas. Beneath its walls we found Mors Umber with a troop of raw green boys, waiting for the king’s coming. He gave us this.”

A girl and an old man, thought Asha, as the two were dumped rudely in the snow before her. The girl was shivering violently, even in her furs. If she had not been so frightened, she might even have been pretty, though the tip of her nose was black with frostbite. The old man … no one would ever think him comely. She had seen scarecrows with more flesh. His face was a skull with skin, his hair bone-white and filthy. And he stank. Just the sight of him filled Asha with revulsion.

He raised his eyes. “Sister. See. This time I knew you.”

Asha’s heart skipped a beat. “Theon?” (The Sacrifice)

Yes, she figures it out quickly. But it remains that at first, Theon is just “an old man”.

Thistle vs. Varamyr

Thistle talks to Varamyr Sixskins about Varamyr Sixskins yet has no idea she is doing so, merely because Varamyr is removed from the context she is used to.

“Harma’s dead and Mance is captured, the rest run off and left us,” Thistle had claimed, as she was sewing up his wound. “Tormund, the Weeper, Sixskins, all them brave raiders. Where are they now?”

She does not know me, Varamyr realized then, and why should she? Without his beasts he did not look like a great man. (DWD Prologue)

Thistle literally names Sixskins to Sixskins, but is clueless, not because Varamyr is disguised—he isn’t, kind of like Arya vis-a-vis Myrcella and Tommen or Catelyn vis-a-vis Jason Mallister—but simply because he lacks context.

People vs. “Famous” People: The Hound and The Mountain

Even The Hound and The Mountain—arguably the most physically recognizable of “knights”—are in fact pointedly not recognized for who they are given the right circumstances. People may suspect and whisper regarding Ser Robert Strong’s identity, but as of now Cersei/Qyburn are getting away with a seeming charade ludicrously involving an 8 foot tall man.

And assuming the Hound is The Gravedigger (duh), Brienne doesn’t recognize him as a grave digging monk on the Quiet Isle despite the fact that he is an infamous, grotesque “knight” she thinks she knows about.

What’s more, thousands of people might say that they “know” that “The Hound” is rampaging in the Riverlands, sacked Saltpans, etc., and hundreds might claim to have witnessed him doing so, but the fact is: Sandor “the Hound” Clegane did no such things. The people who saw “him” saw another man in his armor doing so, and nothing more.

Heraldry and armor is thus often more famous and recognizable than even uniquely memorable “celebrities”.

People vs. “Famous” People: Garlan Tyrell, Renly’s Ghost and Ser Artys Arryn, The Falcon Knight

The Hound’s supposed rampage around Saltpans is not the first time people mistake famous/recognizable (i.e. metaphorically “communicative” or “talking”) armor for the man who they assume wears such armor. As redditor /u/toldschool-bb reminded me, Garlan Tyrell dons Renly’s armor for the Battle of the Blackwater, and most men believe Renly’s Ghost won the day.

“Is it true that Stannis was put to rout by Renly’s ghost?”

Bronn smiled thinly. “From the winch towers, all we saw was banners in the mud and men throwing down their spears to run, but there’s hundreds in the pot shops and brothels who’ll tell you how they saw Lord Renly kill this one or that one. Most of Stannis’s host had been Renly’s to start, and they went right back over at the sight of him in that shiny green armor.” (SOS Tyr I)

Tell it to the bloody singers, with their songs of Renly’s ghost. (SOS Tyr III)

Few know the truth, and even putatively “wiser men” who dismiss foolish talk of ghosts miss the kernel of truth in the popular tale:

The smallfolk say it was King Renly’s ghost, but wiser men know better. It was your father and Lord Tyrell, with the Knight of Flowers and Lord Littlefinger. (COK Tyr XV)

Narry a mention of Garlan. Jaime actually has to dig and wield the oath of the Kingsguard to learn what happened:

As in a swordfight, sometimes it is best to try a different stroke. “It’s said you fought magnificently in the battle . . . almost as well as Lord Renly’s ghost beside you. A Sworn Brother has no secrets from his Lord Commander. Tell me, ser. Who was wearing Renly’s armor?”For a moment Loras Tyrell looked as though he might refuse, but in the end he remembered his vows. “My brother,” he said sullenly. “Renly was taller than me, and broader in the chest. His armor was too loose on me, but it suited Garlan well.” (SOS Jai VIII)

This phenomenon has a legendary precedent in the Battle of the Seven Stars, when The Falcon Knight Ser Artys Arryn’s Andals defeat the First Men led by Bronze King Robar II Royce. Arryn dresses a knight retainer in his spare suit of falcon armor and has him remain visible in the Andal camp. When Royce charges the decoy “Falcon Knight” (resulting in said knight’s death), he opens up his rear to a fatal attack led by the real Falcon Knight. (TWOIAF)

It wasn’t Ser Artys Arryn whom Robar “recognized”, but Arryn’s armor and banners, just as people “recognize” the Hound, Renly’s Ghost and the white-clad Ser Robert Strong.

TWOIAF spends over one text-wall page on this hitherto unknown battle. Chekhov’s Gun strongly suggests there’s a reason for this, and I agree wholeheartedly. [cough-battleofthetrident-cough]

Barristan vs. King’s Landing; Jorah vs. Barristan vs. The Titan’s Bastard

Barristan the Bold—a knight of such great renown that he’s included in Bran and Sansa’s early GOT litanies along with Serwyn the Mirrorshield and Aemon the Dragonknight—tells the story of his escape from and return to King’s Landing, and it’s a showcase of the degree to which “fame” often simply doesn’t matter:

“The men at the gate were taken by surprise. I rode one down, wrenched away his spear, and drove it through the throat of my closest pursuer. The other broke off once I was through the gate, so I spurred my horse to a gallop and rode hellbent along the river until the city was lost to sight behind me. That night I traded my horse for a handful of pennies and some rags, and the next morning I joined the stream of smallfolk making their way to King’s Landing. I’d gone out the Mud Gate, so I returned through the Gate of the Gods, with dirt on my face, stubble on my cheeks, and no weapon but a wooden staff. In roughspun clothes and mud-caked boots, I was just one more old man fleeing the war. The gold cloaks took a stag from me and waved me through. King’s Landing was crowded with smallfolk who’d come seeking refuge from the fighting. I lost myself amongst them. I had a little silver, but I needed that to pay my passage across the narrow sea, so I slept in septs and alleys and took my meals in pot shops. I let my beard grow out and cloaked myself in age. The day Lord Stark lost his head, I was there, watching. Afterward I went into the Great Sept and thanked the seven gods that Joffrey had stripped me of my cloak.” (DWD Dae II)

Shaving and growing beards is something that’s happened much more than we’re told, I believe, and the importance of Barristan’s line about “cloaking himself in age” cannot be overestimated considering how many interesting characters are said to be (or not said to be) “old”. We’re being told that we are wrong to assume general adjectives of age and youth in the text bear some consistent, objective relationship to a careful measure of years rather than to the way a character carries themself or to the role they play. (Consider Cersei thinking Tywin is too old to be Tywin, above.)

Jorah fares little better, failing to recognize Barristan the Bold for quite some time. What he says when he does recognize him is revelatory:

“You know him?” Dany asked the exile knight, lost.

“I saw him perhaps a dozen times … from afar most often, standing with his brothers or riding in some tourney. But every man in the Seven Kingdoms knew Barristan the Bold.” (SOS Dae V)

Every man “knows” him and Jorah even saw him a bunch, yet it’s how. fucking. long before Jorah figures out who Selmy is. And while Selmy’s garb is different and his beard is shaved, he’s less shorn of context than many: still guarding royalty, talking openly and guilelessly about things he clearly has privileged knowledge of. His very name is barely disguised. Still, Mormont is clueless for far longer than many readers would believe possible if it weren’t right there on page, because this is how things work in ASOIAF, as driven home by the fact that Selmy’s unveiling comes on the heels of Barristan’s own failure to recognize the Titan’s Bastard before he could attack Dany, again because of different facial hair.

“Your Grace.” Arstan knelt. “I am an old man, and shamed. He should never have gotten close enough to seize you. I was lax. I did not know him without his beard and hair.”

“No more than I did.” Dany took a deep breath to stop her shaking. (SOS Dae V)

Daenerys, like Selmy and Mormont, is not some unique fool (although perhaps if Littlefinger were here he would intimate as much to the reader, as with Ned and Cat). These are just paradigms of the way even simple disguises work and recognition fails in ASOIAF.

People vs. Slightly-Less-Famous-People: Rosamund and Myrcella

A popular theory is that the current Myrcella is in fact her handmaiden Rosamund. It hinges on this passage:

Rosamund doesn’t truly favor me, but when she dresses up in my clothes people who don’t know us think she’s me.

Sure, she says “people who don’t know us”, and some will leap to insist this means that as soon as anyone’s met them their ruse is impossible, but the remember the title of the essay—He Did Not Know You—and everything we’ve already seen. A clothing switch may not fool, say, Cersei, but people who don’t know them well? That’s a different story.

I’m not going to argue here that they’ve switched places (although yeah, they’ve surely switched). The important takeaway is how they accomplish their ruse: simply by switching clothing a princess of the realm is no longer recognizable as a princess. Why wouldn’t the same be true of others? Don black clothing? You’re a brother of the Watch. Etc. Seems to work for Kingsguards, too.

The Realm vs. The Kingslayer

It’s not just Selmy and the Titan’s Bastard who understand that things like a beards and hair are the primary if not only ways the vast majority of people might ever recognize them without their heraldry, arms and armor. Banners and sigils and custom suits of armor are easily communicated identifying characteristics, whereas a person’s facial structure is difficult to represent (verbally or otherwise), truly known only to some in the first place, and remembered accurately by fewer, especially as time passes. Jaime is a great example:

“You’d be shaved bald?” asked Cleos Frey.

“The realm knows Jaime Lannister as a beardless knight with long golden hair. A bald man with a filthy yellow beard may pass unnoticed. I’d sooner not be recognized while I’m in irons.” (SOS J I)

Jaime actually learns of Joffrey’s death from people who have no idea they are talking to the most infamous knight in the realm, the fucking Kingslayer himself:

The king is dead, they told him, never knowing that Joffrey was his son as well as his sovereign.

“The Imp opened his throat with a dagger,” a costermonger declared at the roadside inn where they spent the night. “He drank his blood from a big gold chalice.” The man did not recognize the bearded one-handed knight with the big bat on his shield, no more than any of them, so he said things he might otherwise have swallowed, had he known who was listening. (SOS Jaime VII)

Notice the coy way we’re set up to momentarily mistakenly infer that people’s ignorance is of Joffrey’s paternity—because “of course” they know Jaime—only to have GRRM yank that impression away in the next paragraph: an emphatic statement about the ease with which even a famous knight can “disappear” should he so choose.

“Half the Court” and Tyrion vs. Jaime

Shorn and physically deteriorated, Jaime wonders if even Tyrion might have failed to recognize him, since “half the court” seems oblivious to his identity as he moves about the Red Keep.

Jaime had spent his days at his brother’s trial, standing well to the back of the hall. Either Tyrion never saw him there or he did not know him, but that was no surprise. Half the court no longer seemed to know him. I am a stranger in my own House. (SOS Jaime VIII)

An examination of Tyrion’s trial chapters demonstrates that Jaime’s suspicions seem well-founded, as Tyrion never notices his own brother in the gallery.

EDIT: Osmund Kettleblack vs. Jaime, Jaime vs. Himself

Osmund’s initial interactions with Jaime epitomize the foregoing phenomena while emphasizing that people (including readers) naturally overemphasize their own capacity to recognize others. Their first encounter, when Jaime is just back from captivity:

Another knight in white armor was guarding the doors of the royal sept; a tall man with a black beard, broad shoulders, and a hooked nose. When he saw Jaime he gave a sour smile and said, “And where do you think you’re going?”

“Into the sept.” Jaime lifted his stump to point. “That one right there. I mean to see the queen.”

“Her Grace is in mourning. And why would she be wanting to see the likes of you?”

Because I’m her lover, and the father of her murdered son, he wanted to say. “Who in seven hells are you?”

“A knight of the Kingsguard, and you’d best learn some respect, cripple, or I’ll have that other hand and leave you to suck up your porridge of a morning.”

“I am the queen’s brother, ser.”

The white knight thought that funny. “Escaped, have you? And grown a bit as well, m’lord?”

“Her other brother, dolt. And the Lord Commander of the Kingsguard. Now stand aside, or you’ll wish you had.”

The dolt took a long look this time. “Is it . . . Ser Jaime.” He straightened. “My pardons, milord. I did not know you. I have the honor to be Ser Osmund Kettleblack.” (SOS Jai VII)

Ser Osmund Kettleblack was the first to arrive. He gave Jaime a grin, as if they were old brothers-in-arms. “Ser Jaime,” he said, “had you looked like this t’other night, I’d have known you at once.”“Would you indeed?” Jaime doubted that. The servants had bathed him, shaved him, and washed and brushed his hair. When he looked in a glass, he no longer saw the man who had crossed the riverlands with Brienne . . . but he did not see himself either. His face was thin and hollow, and he had lines under his eyes. I look like some old man. (SOS Jai VIII)

Sansa vs. Oswell “Kettleblack”

The entire issue of recognition is massively foregrounded by Littlefinger when he presents the “Kettleblack’s” “father” Oswell to Sansa for identification:

“You could turn King’s Landing upside down and not find a single man with a mockingbird sewn over his heart, but that does not mean I am friendless.” Petyr went to the steps. “Oswell, come up here and let the Lady Sansa have a look at you.”

The old man appeared a few moments later, grinning and bowing. Sansa eyed him uncertainly. “What am I supposed to see?”

“Do you know him?” asked Petyr.

“No.”

She studied the old man’s lined windburnt face, hook nose, white hair, and huge knuckly hands. There was something familiar about him, yet Sansa had to shake her head. “I don’t. I never saw Oswell before I got into his boat, I’m certain.”

Oswell grinned, showing a mouth of crooked teeth. “No, but m’lady might of met my three sons.”

It was the “three sons,” and that smile too. “Kettleblack!” Sansa’s eyes went wide. “You’re a Kettleblack!”

“Aye, m’lady, as it please you.” (SOS San VI)

The true beauty of this exchange, in my opinion, is that Oswell Kettleblack is Oswell Whent and that his “sons” are his nephews. I’ve made this case before in passing, and my forthcoming tinfoil will make it exhaustively (I’ve found tons of new evidence), but even at face value we’re being taught a lesson: Sansa’s spent months around three of his close relatives and doesn’t even begin to realize he might be related until he serves it to her on a platter. He was “just” some “old man” serving Littlefinger, so long as he gave her no reason to doubt that’s all he was.

I suspect it’s no accident that GRRM has Sansa think of Oswell over and over as a verbatim “old man” prior to learning the truth, as this speaks to Osmund failing to recognize Jaime but believing he would have under different circumstances, since Jaime then thinks how he has come to look, verbatim, “like some old man”. A la Oswell, then.

Lysa vs. Her Niece, Sansa; Sansa vs. Her Aunt, Lysa

ASOS continues to hammer the rules of recognition when Sansa meets Lysa shortly thereafter. In the first place, Sansa only knows Lysa because she’s told who Lysa is. Even so, she seems to regard Lysa’s physicality as almost alien:

Finally, on a grey windy afternoon, Bryen came running back to the tower with his dogs barking at his heels, to announce that riders were approaching from the southwest. “Lysa,” Lord Petyr said. “Come, Alayne, let us greet her.”

They put on their cloaks and waited outside. The riders numbered no more than a score; a very modest escort, for the Lady of the Eyrie. Three maids rode with her, and a dozen household knights in mail and plate. She brought a septon as well, and a handsome singer with a wisp of a mustache and long sandy curls.

Could that be my aunt? Lady Lysa was two years younger than Mother, but this woman looked ten years older. Thick auburn tresses fell down past her waist, but beneath the costly velvet gown and jeweled bodice her body sagged and bulged. Her face was pink and painted, her breasts heavy, her limbs thick. She was taller than Littlefinger, and heavier; nor did she show any grace in the clumsy way she climbed down off her horse. (SOS San VI)

Meanwhile, Lysa doesn’t show the faintest inkling that “Alayne Stone” might be other than Petyr’s bastard daughter when she’s introduced as such. A bastard doesn’t warrant much thought or a second look:

“My daughter.” Littlefinger beckoned Sansa forward with a hand. “My lady, allow me to present you Alayne Stone.”

Lysa Arryn did not seem greatly pleased to see her. Sansa did a deep curtsy, her head bowed. “A bastard?” she heard her aunt say. “Petyr, have you been wicked? Who was her mother?”…

When Littlefinger reveals Sansa, however, we learn this isn’t for lack of resemblance:

Lady Lysa was still abed, but Lord Petyr was up and dressed. “Your aunt wishes to speak with you,” he told Sansa, as he pulled on a boot. “I’ve told her who you are.”…

Sansa stood by the foot of the bed while her aunt ate a pear and studied her. “I see it now,” the Lady Lysa said, as she set the core aside. “You look so much like Catelyn.”

“It’s kind of you to say so.”

“It was not meant as flattery. If truth be told, you look too much like Catelyn. Something must be done. We shall darken your hair before we bring you back to the Eyrie, I think.“

Having been told who she is looking at, Lysa now decleares that Sansa’s resemblance to Catelyn is so striking (and thus her identity so obvious) that Sansa’s hair must be darkened, yet the night before she didn’t for an instant doubt Petyr’s story that the Cat lookalike was merely Petyr’s bastard daughter by some “wench” of Gulltown.

That speaks volumes about how easy it would be to get away with a disguise in ASOIAF, especially when the passage of time intercedes such that a person’s appearance does, in fact, change with age and time, however subtly.

Littlefinger vs. Lysa and Cat

It’s not some personal failing unique to Lysa that causes her to fail to recognize Sansa. Rather this is simply how recognition “works” in ASOIAF: the same way it does in classic myth, in Arthurian legend, in Shakespeare. After all, one of the more famous instances of non-recognition in the novels is Littlefinger’s failure to recognize Lysa.

Tyrion cocked his head. “Why, every man at court has heard [Littlefinger] tell how he took your maidenhead, my lady.”

“That is a lie!” Catelyn Stark said. (GOT Ty IV)

“That was the night I stole up to [Littlefinger’s] bed to give him comfort. I bled, but it was the sweetest hurt. He told me he loved me then, but he called me Cat, just before he fell back to sleep.” – Lysa Tully (SOS San VII)

The Golden Company vs. Jon Connington

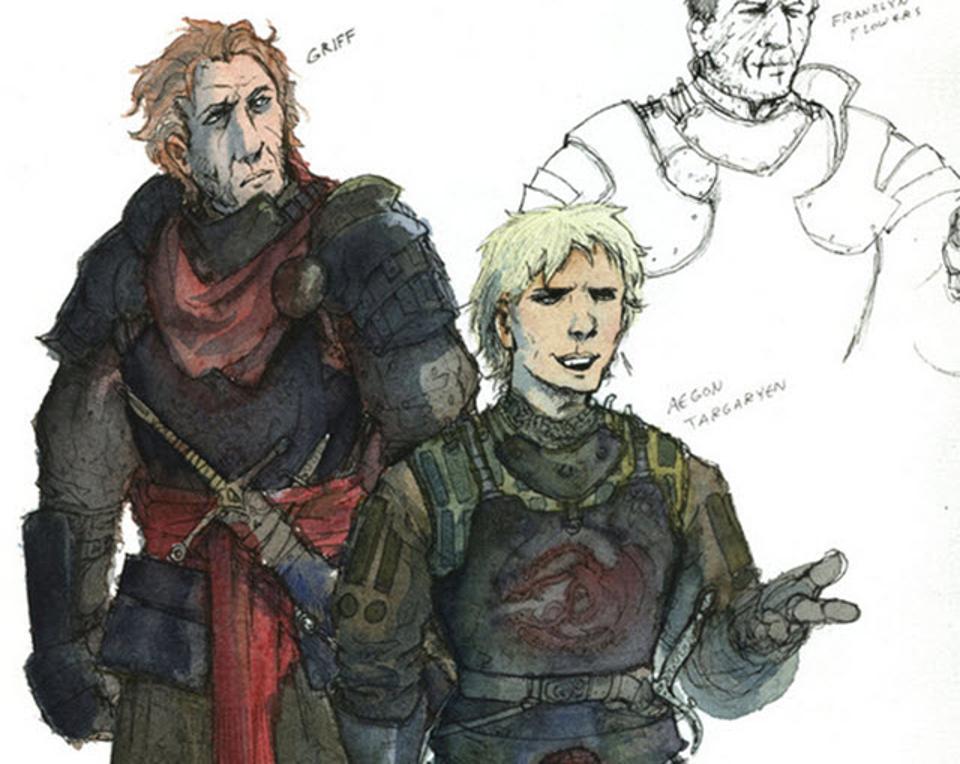

“Griff” counts on something similar the entire time he’s “dead”. His thoughts highlight the in-world logic as to why things as simple as a shave and a dye job can keep a man hidden, but even if you don’t personally think his logic is sound, the fact that he successfully “drank himself to death” and disappeared tells you how ASOIAF functions:

The men of the Golden Company were outside their tents, dicing, drinking, and swatting away flies. Griff wondered how many of them knew who he was. Few enough. Twelve years is a long time. Even the men who’d ridden with him might not recognize the exile lord Jon Connington of the fiery red beard in the lined, clean-shaved face and dyed blue hair of the sellsword Griff. So far as most of them were concerned, Connington had drunk himself to death in Lys after being driven from the company in disgrace for stealing from the war chest. (DWD tLL)

Pycelle’s Beard

When Tyrion shaves Pycelle’s beard, there’s no question of the Grand Maester’s identity, but there’s also no question but that the shave profoundly alters Pycelle’s appearance. Jaime literally states that it’s intrinsic to Pycelle’s identity.

Without his beard, Pycelle looked not only old, but feeble. Shaving him was the cruelest thing Tyrion could have done, thought Jaime, who knew what it was to lose a part of yourself, the part that made you who you were. Pycelle’s beard had been magnificent, white as snow and soft as lambswool, a luxuriant growth that covered cheeks and chin and flowed down almost to his belt. The Grand Maester had been wont to stroke it when he pontificated. It had given him an air of wisdom, and concealed all manner of unsavory things: the loose skin dangling beneath the old man’s jaw, the small querulous mouth and missing teeth, warts and wrinkles and age spots too numerous to count. Though Pycelle was trying to regrow what he had lost, he was failing. Only wisps and tufts sprouted from his wrinkled cheeks and weak chin, so thin that Jaime could see the splotchy pink skin beneath. (FFC Jai I)

Were he no longer chained but instead turned loose in plain garb, who would believe this is the Grand Maester of the Seven Kingdoms?

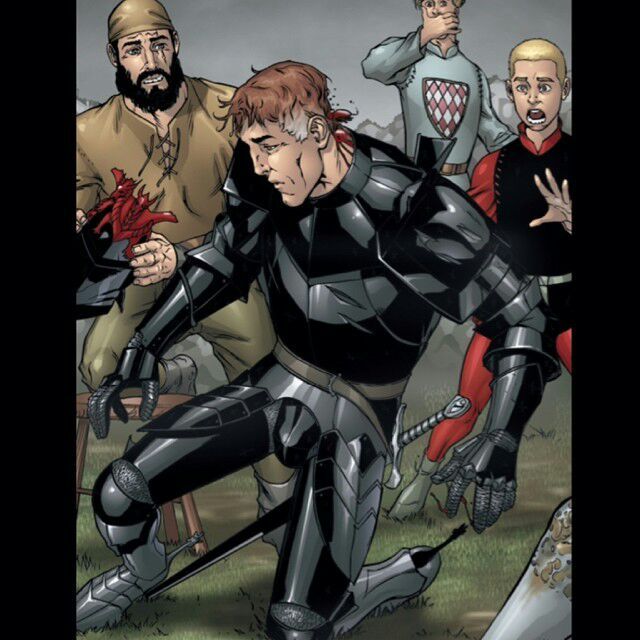

Dunk the Lunk vs. Baelor Breakspear and Egg/Aegon

The first half of the short story The Hedge Knight is essentially dedicated to the themes I’m arguing will pay-off in major revelations of hidden identity. It takes Dunk—Duncan the Tall—forever to learn that the “stable boy” he’s allowing to squire for him is in fact the Targaryen prince Aegon. Aegon’s just a kid, and he takes the precaution of pre-figuring Rodrik, Selmy and the Titan’s Bastard by shaving his identifiable hair, allowing him to freely mingle with the commons on the tourney ground, so Dunk’s mistake is (again) not unique, and also understandable, even predictable

More to the point, though, Dunk also meets Crown Prince Baelor Breakspear, the most famous knight in the kingdom, a man Dunk actively thinks about at the time:

Valarr was the eldest son of Prince Baelor, second in line to the Iron Throne, but Dunk did not know how much of his father’s fabled prowess with lance and sword he might have inherited.…

Dunk knew Prince Baelor was older, but the youth [actually Aerion, Maekar’s son] might well have been one of his sons:

Even with Baelor on his mind, Dunk completely fails to recognize him despite the fact that he watches him argue with Maekar (a more obvious Targ prince who calls him “brother”), speak with easy familiarity about Targaryens, refer to “Daeron” as “your blood and mine,” and sit in the “high seat” of the great hall of Ashford Castle.

Why doesn’t Dunk realize who Baelor is (or even, generically, what he is)? “Because he’s a lunk, stupid!” No. (But his characterization cleverly allows and invites that interpretation.) It’s because Baelor doesn’t look like Dunk expects a Targaryen to look.

Dunk could see the speaker now. He was seated in the high seat, a sheaf of parchments in one hand, Lord Ashford hovering at his shoulder. Even seated, he looked to be a head taller than the other, to judge from the long straight legs stretched out before him. His short-cropped hair was dark and peppered with grey, his strong jaw clean-shaven. His nose looked as though it had been broken more than once. Though he was dressed very plainly, in green doublet, brown mantle, and scuffed boots, there was a weight to him, a sense of power and certainty.

Baelor treats Dunk with far more respect and dignity than the other less powerful lords, and admits to having jousted Ser Arlan, for whom Dunk squired. Dunk’s moment of revelation/recognition is cute:

“It was nine years past, at Storm’s End. Lord Baratheon held a hastilude to celebrate the birth of a grandson. The lots made Ser Arlan my opponent in the first tilt. We broke four lances before I finally unhorsed him.

“Seven,” insisted Dunk, “and that was against the Prince of Dragonstone!” No sooner were the words out than he wanted them back. Dunk the lunk, thick as a castle wall, he could hear the old man chiding.

“So it was.” The prince with the broken nose smiled gently. “Tales grow in the telling, I know. Do not think ill of your old master, but it was four lances only, I fear.”

Dunk was grateful that the hall was dim; he knew his ears were red. “My lord.” No, that’s wrong too.

“Your Grace.” He fell to his knees and lowered his head. “As you say, four, I meant no . . . I never … The old man, Ser Arlan, he used to say I was thick as a castle wall and slow as an aurochs.”

“And strong as an aurochs, by the look of you,” said Baelor Breakspear. “No harm was done, ser. Rise.”

Dunk got to his feet, wondering if he should keep his head down or if he was allowed to look a prince in the face. I am speaking with Baelor Targaryen, Prince of Dragonstone, Hand of the King, and heir apparent to the Iron Throne of Aegon the Conqueror.

Again, what GRRM does here is brilliant: he shows us that recognition is not nearly as easy as we might think in a world without reproducible, disseminatable images, while simultaneously inviting us to glide over that key theme (and its delicious implications) and focus instead only on the idiosyncrasies of the situation—specifically on the fact that Duncan’s failure is due to the fact that he is, as he says, “Dunk the lunk, thick as a castle wall”.